Pokémon Red / Blue (Game Boy) Review

By Mike Mason  17.03.2006

17.03.2006

Picture the scene. It's 1995, Playstation has recently hit and Nintendo's Game Boy is slowly disappearing from the mainstreams' eyes. Normally, once a decline has begun, there is no way back, with popularity tumbling until the format is dead, but in an exceptional turn around the handheld went from dying to one of the most profitable product lines in video gaming. The sole reason for this? Pokémon.

As a child, have you ever caught a creature – a butterfly, perhaps? It doesn’t matter whether you held onto it for just a few seconds, or tried to keep it as a pet (or pinned it to a page in a book if you’re that way inclined), you have still adhered to the human instincts of exploration and wanting to be in control of something other than yourself. Satoshi Tajiri was no different to the rest of us, and his curiosity was satisfied by sifting through small rock pools, grass and the like for tiny bugs and shellfish. Being from the urban land of Japan, these rural hunts were an escape for him, and the thoughts that it brought to him stuck in his mind even when he grew out of the practice. Later in life, he realised his ambition to create games and formed a company, Game Freak, so that he could get his ideas out to the world.

Beavering away for years, Tajiri caught the attention of Nintendo – specifically your hero and ours, Shigeru Miyamoto. Intrigued by his ideas, Nintendo signed him up and had him continue his game for the Game Boy, in hopes of bringing it back to life. Pokémon was that game, and featured you playing as a 10-year old boy intent on becoming a Pokémon Master; that is, to beat the Pokémon League and collect all of the monsters – 150 of the critters, to be exact. How could one beat the Pokémon League, you ask? Well, there’s a reason they were just referred to as ‘monsters’ – these fellas fight. Each is assigned an elemental type (two if they’re greedy), each with its own strengths and weaknesses. For example, a Fire type can scorch a Grass type, who can suck the life out of a Water type, who in turn can douse the flames of a Fire type. It all works in one big game of Rock-Paper-Scissors, and these are not the only types either, with around 15 in total – even though there are quite a few types, it never gets overly complex. These include Psychics, Electric based creatures and, of course, straight from Tajiri’s childhood, Bugs. To get far you cannot rely on a single monster, and must add some from every type to your arsenal.

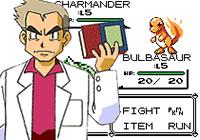

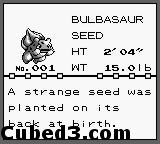

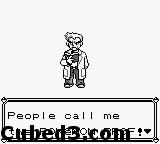

You are given a creature to start with at the beginning of the game by the kindly local Pokémon expert, Professor Oak, after trying to leave the town you grew up in without one (kids today…). You can choose from a Charmander (small, fire breathing lizard), a Bulbasaur (dinosaur with a grassy bulb on its back) and a Squirtle (blue turtle – this little guy really drew the short straw for imagination out of the starters) – all will become powerful with enough training, so it’s really down to personal preference which one you pick. Your childhood rival also grabs a monster and away you can go on your adventure (interestingly, a default name for your character is Satoshi, while a default name for your rival is Shigeru – this was Tajiri’s way of showing Miyamoto appreciation for his help in making the game). This one creature can’t see you through on its own though, as mentioned earlier, and you must capture more in the wild to help out. To do this, you wander through tall grass until an enemy monster appears in a battle sequence (the frequency of these can be really quite irritating when you’re trying to get somewhere). Beat it down sufficiently without knocking it out, throw a Pokéball and it could be yours. Pokéballs are the means to hold these creatures and shrink them down for ease of transport; the name Pokémon is a compound of ‘pocket’ and ‘monsters’ due to the size of them when they’re stored in these balls. Up to six Pokémon can be held with you at any one time, with anymore that you capture going off to be stored at Oak’s lab until you call for them (this is done by connecting to a network on a computer and swapping the balls around with a natty teleportation device). If all six of your creatures faint during battle, you black out, lose half of your money and wake up outside a Pokémon Centre. So don’t.

Wild Pokémon aren’t the only things you can fight, though. Rival trainers are spread across the land, each wanting to try their hand at beating you. See them off and there are more important trainers to battle, gym leaders. There are eight of these, one in most towns or cities, who have to be beaten to gain badges which allow access to the Pokémon League. By causing the enemies’ monsters to faint (no Pokémon were hurt during the making of this game – awww), your monsters gain valuable experience points. Oh yes, an RPG in the purest sense of the word, statistics are a huge part of the game – this may sound daunting, but it really isn’t. There are a few visible statistics that determine how well your beasts do in battle (and a few invisible ones behind the code that were found by some extremely clever people/people with nothing better to do): Attack determines how much damage your physical attacks cause, Defence influences how much damage from physical attacks you can sustain, Speed lets you know who attacks first in each round (the monster with the highest value does) and Special lets you know how much harm you can dish out and how much you can take when using elemental attacks. To add another layer of strategy, these base values can all be temporarily increased or decreased by using certain moves within battles – speaking of which, the battle system has yet to be fully explained. Matches are turn based, with trainers able to use up to six Pokémon each to try and best their foes. The creatures you use have to be carefully planned, as they will all have their good points and bad points, as well as a specific set of moves; each one is allowed just four moves, which can be learnt naturally as they gain levels from experience or taught using special items called TMs (Technical Machines). Choose those moves wisely, now…

While 150 species might seem like overkill (and there are a couple of hundred more now in the newer iterations of the series), it isn’t so bad once you learn of the families. Many of the animals are related to others and as they grow in level they may evolve into more potent allies; for example, a starter mentioned earlier, Charmander, can grow from a little lizardy wuss into a ginormous fire breathing dragon who wouldn’t hesitate to snap your tasty little head off if you don’t keep it under control, perhaps with threats of a Super Soaker to its bonce. Other evolutions can take place with exposure to specific items, or automatically after a trade. With these evolutions, some statistics increase while others decrease, and in an extra element of strategy you can cancel evolutions, choosing to hold them off until you’re certain that it cannot improve anymore in its current state. The levels of customisation demonstrated by this and the number of moves available mean that it’s possible to come back time and time again and do things just a little differently – every time is satisfying, and the possibilities are quite near endless.

Trading is the feature that truly made Pokémon as big as it is. By connecting two Game Boys with a link cable, players can enter a Pokémon Centre (also used to heal tired monsters) and enter an area where you can trade creatures with people, or test your battling skills. This is the only way to get certain Pokémon, as there are several creatures that are exclusive to each version – a big incentive to get your friends to buy the version that you didn’t get. It worked, too, as Nintendo’s bank balances will probably testify.

Pokémon was the game that deserved to be the one to revive the Game Boy platform and deserved to become one of Nintendo’s regular franchises. Balancing a complex system with a huge variety of possible combinations of beasts and moves while still retaining a reasonably simplistic and easy to pick up game is not an easy feat, but somehow Tajiri and his company managed it to create a game that rightfully is considered a masterpiece. While later versions such as Gold/Silver and Ruby/Sapphire added more elements and improved gameplay in almost every way, none have the landmark appeal that the originals do – they are the ones that belong in the gaming halls of fame.

Cubed3 Rating

Exceptional - Gold Award

The original Game Boy's finest moment, almost cooked to perfection, with the raw sides being grilled to flawlessness in the sequels on the Game Boy Colour. If you think this game is for kids, play it and guess again; it fits into the Nintendo philosophy of 'anybody can play', and everybody should play this. Impeccable.

![]() 9/10

9/10

![]() 9/10

(19 Votes)

9/10

(19 Votes)

Out now

Out now  Out now

Out now  Out now

Out now  Out now

Out now Comments

Comments are currently disabled

Sign In

Sign In Game Details

Game Details Subscribe to this topic

Subscribe to this topic Features

Features

Top

Top